|

| Madhavi PC The Hindu |

Silappadikaram: Treasure Trove of Music and Dance

Silapadikaram (‘The Story of Anklet’), composed by Ilango adigal (இளங்கோ அடிகள்), the Jain poet-prince from Chera country, is considered as the treasure trove of information on music and dance, (both classical and folk) of the period, dealing in great detail with the intricacies and techniques involved. It contains three chapters and a total of 5270 lines (13,870 words) of poetry. The epic, as in Sangam poems, do not revolve around the five land divisions (திணை) (Kurinji (குறிஞ்சி), Mullai (முல்லை), Marudam (மருதம்), Neidal (நெய்தல்) and Palai (பாலை). Instead it adopts the novel convention of considering the geographical and political divisions of Tamil country i.e., Chola (சோழர்), Pandya (பாண்டியர்) and Chera (சேரர்) in relation to their capitals i.e., Poompukar (பூம்புகார்), Madurai (மதுரை), and Vanji (வஞ்சி). Thus the epic was aptly divided into three Kandams (Cantos) i.e., Pukark-kandam (புகார்க் காண்டம் – Pukar canto), Maduraik-kandam (மதுரைக் காண்டம் – Madurai canto) and Vanchik-kandam (வஞ்சிக் காண்டம் – Vanchi canto). It uses akaval meter (monologue) (அகவற்பா), a style adopted in most poems in Sangam literature. Adiyarkk unallar (அடியார்க்கு நல்லார்), renowned Silappadikaram commentator, delineated the essential nature of poems by virtue of content that forms a unity of having elements of poetry (iyal), music (isai) and drama (natakam) (இயல் இசை நாடக பொருள் தொடர் நிலை செய்யுள்).

The date is assignable to 2nd century AD. U. V. Swaminatha Iyer (உ.வே சுவாமிநாத அய்யர்) (1855-1942 CE) found that the ancient Tamil poems in palm leaf manuscripts left in a state of neglect and gradual destruction. The Tamil scholar resurrected Silappadikaram from palm leaf format and reprinted the epic from palm leaf format to paper book format in 1892 AD. So we are familiar with the printed book of this epic for the past 124 years only.

The epic is attributable for standardizing the folk songs to literary genre. The epic also details about``yazh'' (14 stringed instrument - lute) as well as various various Panns, their grammar and demonstrates how different compositions of swaras to result into different ragas with the help of the ``yazh'

Silappadikaram is the first Tamil epic composed about the life of an ordinary countryman. Kovalan was the son of the merchant prince Masathuvan (மாசாத்துவான்)

மண்தேய்த்த புகழினான் மதிமுக மடவார்தம்

பண்தேய்த்த மொழியினார் ஆயத்துப் பாராட்டிக்

கண்டுஏத்தும் செவ்வேள்என்று இசைபோக்கிக் காதலால்

கொண்டுஏத்தும் கிழமையான் கோவலன்என் பான்மன்னோ.

Kannagi was the daughter of the celebrated sea captain Manaikan (மாநாய்கன்).

போதில்ஆர் திருவினாள் புகழுடை வடிவென்றும்

தீதிலா வடமீனின் திறம்இவள் திறம்என்றும்

மாதரார் தொழுதுஏத்த வயங்கிய பெருங்குணத்துக்

காதலாள் பெயர்மன்னும் கண்ணகிஎன் பாள்மன்னோ,

"The beauty of this damsel is like that of goddess Lakshmi who dwells on the lotus. Her virtue is truly like that of the North Star. She was in love with goodness; her name was Kannagi."

|

| Kannagi Kovalan Wedding Procession PC Vallamai |

மாலைதாழ் சென்னி வயிரமணித் தூணகத்து

நீல விதானத்து நித்திலப்பூம் பந்தர்க்கீழ்

வான்ஊர் மதியம் சகடுஅணைய வானத்துச் 50

சாலி ஒருமீன் தகையாளைக் கோவலன்

மாமுது பார்ப்பான் மறைவழி காட்டிடத்

தீவலம் செய்வது ... ..

The parents of of Kovalan and Kannagi celebrated the marriage on an auspicious day on which the Rohini star joins the moon. In a hall with gem studded pillars, decorated with flower garlands hanging above, under the canopy of blue silk and pearls, with the preceptor guiding him, Kovalan married Kannagi. The couple united like the god of love and his spouse and lived together happily for some time. Kovalan's parents gave a part of the family wealth along with a number of servitors and helped them set up their own household. Kannagi managed her household in a praiseworthy manner. |

| Kovalan - Madhavi |

மணமனை புக்கு மாதவி தன்னொடு

அணைவுறு வைகலின் அயர்ந்தனன் மயங்கி

விடுதல் அறியா விருப்பினன் ஆயினன்.

வடுநீங்கு சிறப்பின்தன் மனையகம் மறந்து

சலம்புணர் கொள்கைச் சலதியொடு ஆடிக்

குலம்தரு வான்பொருள் குன்றம் தொலைந்த

இலம்பாடு நாணுத் தரும்

சிலம்பின் செய்வினை யெல்லாம்

பொய்த்தொழிற் கொல்லன் புரிந்துடன் நோக்கிக்

கோப்பெருந் தேவிக் கல்லதை இச்சிலம்பு

யாப்புற வில்லை யெனமுன் போந்து

விறல்மிகு வேந்தற்கு விளம்பியான் வரவென்

சிறுகுடி லங்கண் இருமின்

Kovalan was accused as the thief (சிலம்பு கொண்ட கள்வன்). The Pandyan sent his guards to apprehend Kovalan and the guards killed Kovalan and taken the anklet to Pandya's court.

... ... என்

தாழ்பூங் கோதை தன்காற் சிலம்பு

கன்றிய கள்வன் கைய தாகில்

கொன்றச் சிலம்பு கொணர்க

கல்லாக் களிமக னொருவன் கையில்

வெள்வாள் எறிந்தனன் விலங்கூ டறுத்தது

... ... ...

... ... ...

காவலன் செங்கோல் வளைஇய வீழ்ந்தனன்

கோவலன் பண்டை ஊழ்வினை உருத்தென்.

|

| Kannagi in Pandya Court PC Vallamai |

பொங்கி எழுந்தாள் விழுந்தாள் ....

செங்கண் சிவப்ப அழுதாள்

Commentary of Adiyakku Nallar on Koothu

In the third chapter, Arangetrukaadai” (அரங்கேற்று காதை) or “the debut on-stage performance,” details the knowledge and skills necessary for a dancer, dance master (ஆடல் ஆசான்), the composer of verses (பாடல் ஆசிரியர்), the drummer (percussion) instrumentalist (தண்ணுமை (மிருதங்கம்) என்னும் தாளவிசைக் கருவி வாசிப்பவர்), flutist (புல்லாங்குழல் (வாய்க்காற்றால் ஊதி இசைக்கப்படும் கருவி) வாசிப்பவர்) and yazh (lute) (string) instrumentalist (யாழ் நரம்பு இசைக்கருவி வாசிப்பவர்).

இருவகைக் கூத்தின் இலக்கணம் அறிந்து

பலவகைக் கூத்தும் விலக்கினிற் புணர்த்துப்

பதினோர் ஆடலும் பாட்டும் கொட்டும்

விதிமாண் கொள்கையின் விளங்க அறிந்து

The dance master should know the nuances of the two 'koothus' i.e., Aka-koothu (அகக்கூத்து) and Pura-koothu (புறக்கூத்து). Aka-koothu, also known as 'Vettiyal-koothu,' (வேத்தியல் கூத்து) will be performed in royal courts before king and the royal court-officials. Pura-koothu, also known as 'Pothuviyal-koothu,' (பொதுவியல் கூத்து) will be performed before common mass. The dance master should also be proficient in eleven modes of dances: 1.Kadayam (கடையம்), 2. Marakkal (மரக்கால்), 3.Kudai (குடை), 4.Thudi (துடி), 5.Mal (மால்), 6.Alliam (அல்லியம்), 7.Kumbam / kudam (கும்பம் / குடம்), 8.Pedu (பேடு), 9.Pavai (பாவை): 10. Pandarangam (பாண்டரங்கம்), and 11. Kodukotti (கொடுகொட்டி). A Tamil poem helps one to remember these eleven dance modes: பலவகைக் கூத்தும் விலக்கினிற் புணர்த்துப்

பதினோர் ஆடலும் பாட்டும் கொட்டும்

விதிமாண் கொள்கையின் விளங்க அறிந்து

'கடையம், அயிராணி மரக்கால்விந்தை, கந்தன், குடை, துடிமால், அல்லியமல், கும்பம் - சுடர்விழியால் பட்டமதன் பேடுதிருப் பாவை அரண் பாண்டரங்கம் கொட்டியிவை காண்பதினோர் கூத்து'

Adiyarkku Nallar (12th / 13th century AD), renowned commentator, covers the entire work of Silappadikaram and cites the ancient Tamil works on verse, prose and drama in his commentary. The commentator details the koothus in pairs:

1. Vettiyal (வேத்தியல்) against Pothuviyal (பொதுவியல்); 2. Santhi koothu (சாந்திக் கூத்து) against Vinotha koothu (விநோதக் கூத்து); 3. Vari koothu (வரிக்கூத்து) against Vari-Santhi koothu (வரிசாந்திக் கூத்து); 4. Vasai koothu (வசைக் கூத்து) against Pukal koothu (புகழ்க் கூத்து); 5. Ariya koothu (ஆரியக் கூத்து) against Tamil koothu (தமிழ்க் கூத்து); 6. Eyalpu koothu (இயல்புக் கூத்து) against Desi koothu (தேசிக் கூத்து).

1. Vettiyal (வேத்தியல்) against Pothuviyal (பொதுவியல்); 2. Santhi koothu (சாந்திக் கூத்து) against Vinotha koothu (விநோதக் கூத்து); 3. Vari koothu (வரிக்கூத்து) against Vari-Santhi koothu (வரிசாந்திக் கூத்து); 4. Vasai koothu (வசைக் கூத்து) against Pukal koothu (புகழ்க் கூத்து); 5. Ariya koothu (ஆரியக் கூத்து) against Tamil koothu (தமிழ்க் கூத்து); 6. Eyalpu koothu (இயல்புக் கூத்து) against Desi koothu (தேசிக் கூத்து).

Santhi koothu (சாந்திக் கூத்து) comprise four kinds of koothus i.e., 1. Chokam (சொக்கம்), 2. Mei koothu (மெய்க் கூத்து), 3. Abinaya (அவிநயம்) and 4. Natakam (நாடகம்). Chokam, also known as 'Suddha Nrittam,' (சுத்த நிருத்தம்) which constitutes '108 Thandava Karanas' (108 தாண்டவ கரணங்கள்) Mei koothu (மெய்க் கூத்து) is made up of dumb-shows with gesticulations and conventional posturing. Abhinaya (அவிநயம்) depicts in action and poses, the feelings and sensations as experienced by the person, as described by the words of the songs. Abinaya includes both Rasa-abinaya and Vachika-abinaya. Natakam relates to huge story or epic. The play is divided into many scenes of poems and conversations. Natakam (நாடகம்) is based on Sanskrit and Tamil literature. Since Vinotha koothu (விநோதக் கூத்து) is oriented towards entertainment, fun and play, it incorporates some quantity of artful trickery and jugglery i.e., balancing on rope, puppetry, balancing tiers of pots on the head etc., It includes seven variants: 1. Kuravai koothu (குரவைக் கூத்து), 2. Kallai koothu (கல்லைக் கூத்து), 3. Kuda koothu (குடக் கூத்து), 4. Karanam (கரணம்), 5. Nokku (நோக்கு), 6. Thodpavai Koothu (தோற்பாவைக் கூத்து) and 7. Vinotha koothu(விநோதக் கூத்து).

Vari koothu (வரிக்கூத்து) is performed by actors with songs (pieces of poems set into music) with occasional interludes. 1. Kurathi pattu (குறத்தி பாட்டு) and 2. Ulathi pattu (உழத்தி பாட்டு) are specific Tamil poetic compositions. Vari-Santhi koothu (வரிசாந்திக் கூத்து) is the variation of Vari-koothu.

Vasai koothu (வசைக் கூத்து) deals with satire and Pukal koothu (புகழ்க் கூத்து) deals with eulogizing or praise formally and eloquently.

Vari koothu (வரிக்கூத்து) is performed by actors with songs (pieces of poems set into music) with occasional interludes. 1. Kurathi pattu (குறத்தி பாட்டு) and 2. Ulathi pattu (உழத்தி பாட்டு) are specific Tamil poetic compositions. Vari-Santhi koothu (வரிசாந்திக் கூத்து) is the variation of Vari-koothu.

Vasai koothu (வசைக் கூத்து) deals with satire and Pukal koothu (புகழ்க் கூத்து) deals with eulogizing or praise formally and eloquently.

Ariya koothu (ஆரியக் கூத்து) stands for the narratives from Ramayana and Mahabharata. Tamil koothu (தமிழ்க் கூத்து) stands for Tamil folklore narratives like Sudalai Madan.

Desi koothu (தேசிக் கூத்து) include three variants; 1. Desi koothu (தேசிக் கூத்து), 2. Vadaku koothu and Singhalam koothu (சிங்களக் கூத்து). Desi koothu (தேசிக் கூத்து) involves the dance of Tamil country, Vadaku koothu (வடக்குக் கூத்து), is also known as Marka koothu (மார்க்கக் கூத்து), and is well known as the dance of the Telugu country, whilst Singhala was regarded as the dance of the Singhala country.

“Arangetrukaadai” or “the debut on-stage performance”

In the third chapter, “Arangetrukaadai” (அரங்கேற்று காதை) or “the debut on-stage performance”, Madhavi got ready for her maiden dance performance before the court of the Chola king Karikalan at Poompukar, the Chola capital. The chapter narrates in great details the debut performance and the entire text has extensive references to technical terms connected to dance and music.

Danseuse Madhavi (மாதவி) was the daughter of Chitrapathy (சித்ரபதி) and she hailed from Kanigaiyar (கணிகையர்) tradition (a Devadasi family). Arangetrukaadai traces how by the curse of sage Agathiya (அகத்தியர்), Urvasi (ஊர்வசி) (celestial dancer) and Jayanthan (ஜயந்தன்) (son of Lord Indra) were born as Madhavi (மாதவி), the dance heroine, and Thalaikol (தலைக்கோல் ) respectively. She is celebrated in the line of descent of Urvasi and is called Vanavamakal (divine woman). She learned dance from the age of five and mastered the classical dance at the age of twelve. Madhavi’s debut dance (arangetram) took place at Poompukar, the capital of the Chola Kingdom, in the presence of the Chola King, the learned assembly and the citizens. After the rigorous full time training for seven years under the able guidance of the dance master (ஆடல் ஆசான்) she was fit enough to exhibit her dance before the Chola king.

பிறப்பிற் குன்றாப் பெருந்தோள் மடந்தை

தாதுஅவிழ் புரிகுழல் மாதவி தன்னை

ஆடலும் பாடலும் அழகும் என்றுஇக்

கூறிய மூன்றின் ஒன்றுகுறை படாமல்

ஏழாண்டு இயற்றிஓர் ஈராறு ஆண்டில் 10

சூழ்கடல் மன்னற்குக் காட்டல் வேண்டி (Silappadikaram, Aragetru Kadhai (6-11)

Madhavi's dance master should know the nuances of the two 'koothus' i.e., Aka-koothu (Vettiyal koothu) and Pura-koothu (Pothuviyal koothu), The master should harmonize various kinds of dance forms with proper songs. He must be proficient in the eleven modes of dance as well as music and percussion instruments as prescribed in the relevant prescript. The master should aware the appropriate occasion to apply the hand gestures such as 1. pindi (பிண்டி), 2. pinayal (பிணையல்), 3. ezhirkai (எழிற்கை) and 4. thozhirkai (தொழிற்கை).

The music teacher (இசை ஆசிரியர்) of Madhavi should be skilled enough in playing on the yazh (lute) and flute in accordance with the rhythm and vocal music. He should also be skilled in playing low sounding tabor and in harmonizing the songs with the musical instruments. The music teacher should be knowledgeable in the pronunciation of the words of the languages. The composer of the song should be conversant in Tamil language and be familiar with the rules of grammar of the two categories of dance: Vettiyal and pothuviyal

The percussion instrumentalist (drummer) (தண்ணுமை இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be proficient and knowledgeable in the dance forms, lyrical compositions, music, Tamil literature. He should play on the instrument in such a way to keep the tempo doubled with the rhythm kept intact. The drummer should play the instrument to perfectly to harmonize with the yazh (lute) and flute sounds as well as the vocalist's voice. The flute player should be conversant with the prescribed rules of the flute-music. The flutist (குழல் இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be proficient in the two kinds of manipulations i.e., chittiram and vanjanai by which the harsh sounds of the song are made pleasing to the ear. The yazh player (யாழ் இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be skilled in playing yazh with fourteen strings, arrange in the right order which could produce the palai scales. Silappadikaram mentions about four different kinds of yazhs (lute): 1. mulari yazh 2 sruthi veenai 3 Parijatha veenai 4 Chathurthandi veenai.

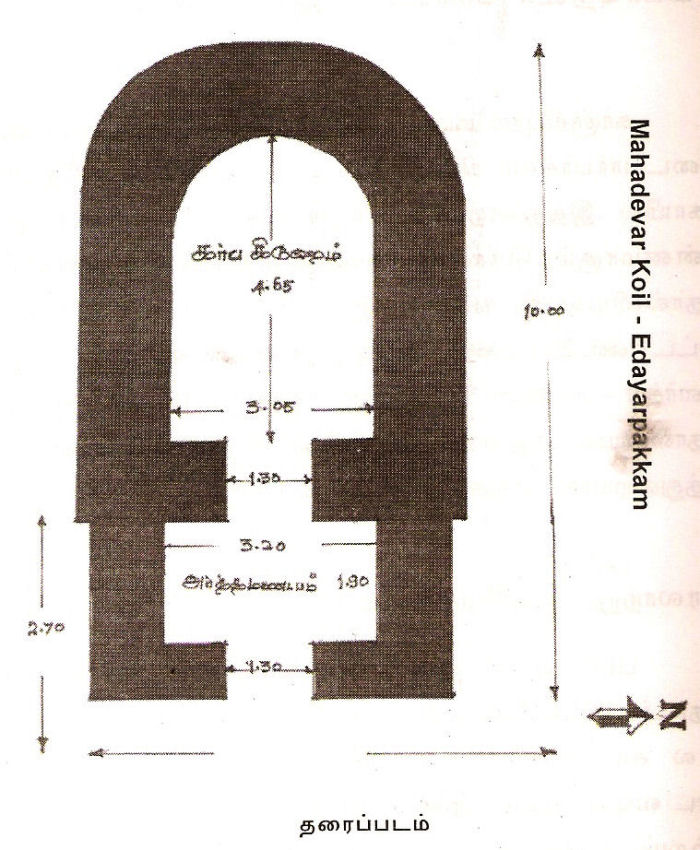

The site for the construction of the dance stage chosen in conformity with the authoritative rules and directions. They have employed the measuring rod measuring about twenty four thumb breadth long. The measuring rod was cut out of a tall bamboo with a span long between two joints. The stage was eight rods in length, seven rods in breadth and one rod in height. The plank placed above the pillars was four rods above the platform. The stage was provided with two appropriate doors. Above the stage were placed the pictures of the demons worthy of worship. The graceful lighting up the stage was so located that the shadow cast by the pillars did not darken the auditorium. The stage was fitted with single-side screen, a double-side screen, and a concealed, over-hanging screen. It had a finely-painted ceiling, and the garlands of pearls hung all over.

Talaikkol, the sacred rod made of bamboo, would be wielded by the dance-master to regulate the dance. The shaft represents Jayanta, Indra’s son who according to legend, was cursed by Sage Agastya to be born as a bamboo stick. Talaikkol was invariably the shaft of the umbrella of the enemy king and was seized in war.

ஆடலும் பாடலும் பாணியும் தூக்கும்

கூடிய நெறியின கொளுத்துங் காலைப்

பிண்டியும் பிணையலும் எழிற்கையும் தொழிற்கையும்

கொண்ட வகைஅறிந்து கூத்துவரு காலைக்

கூடை செய்தகை வாரத்துக் களைதலும்

வாரம் செய்தகை கூடையிற் களைதலும்

பிண்டி செய்தகை ஆடலிற் களைதலும்

ஆடல் செய்தகை பிண்டியிற் களைதலும்

குரவையும் வரியும் விரவல செலுத்தி

ஆடற்கு அமைந்த ஆசான் (Silappadikaram, Aragetru Kadhai (16-25)

The percussion instrumentalist (drummer) (தண்ணுமை இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be proficient and knowledgeable in the dance forms, lyrical compositions, music, Tamil literature. He should play on the instrument in such a way to keep the tempo doubled with the rhythm kept intact. The drummer should play the instrument to perfectly to harmonize with the yazh (lute) and flute sounds as well as the vocalist's voice. The flute player should be conversant with the prescribed rules of the flute-music. The flutist (குழல் இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be proficient in the two kinds of manipulations i.e., chittiram and vanjanai by which the harsh sounds of the song are made pleasing to the ear. The yazh player (யாழ் இசைக் கலைஞர்) should be skilled in playing yazh with fourteen strings, arrange in the right order which could produce the palai scales. Silappadikaram mentions about four different kinds of yazhs (lute): 1. mulari yazh 2 sruthi veenai 3 Parijatha veenai 4 Chathurthandi veenai.

The site for the construction of the dance stage chosen in conformity with the authoritative rules and directions. They have employed the measuring rod measuring about twenty four thumb breadth long. The measuring rod was cut out of a tall bamboo with a span long between two joints. The stage was eight rods in length, seven rods in breadth and one rod in height. The plank placed above the pillars was four rods above the platform. The stage was provided with two appropriate doors. Above the stage were placed the pictures of the demons worthy of worship. The graceful lighting up the stage was so located that the shadow cast by the pillars did not darken the auditorium. The stage was fitted with single-side screen, a double-side screen, and a concealed, over-hanging screen. It had a finely-painted ceiling, and the garlands of pearls hung all over.

நூல்நெறி மரபின் அரங்கம் அளக்கும்

கோல்அளவு இருபத்து நால்விரல் ஆக 100

எழுகோல் அகலத்து எண்கோல் நீளத்து

ஒருகோல் உயரத்து உறுப்பினது ஆகி

உத்தரப் பலகையொடு அரங்கின் பலகை

வைத்த இடைநிலம் நாற்கோல் ஆக

ஏற்ற வாயில் இரண்டுடன் பொலியத் 105

தோற்றிய அரங்கில் தொழுதனர் ஏத்தப்

பூதரை எழுதி மேல்நிலை வைத்துத்

தூண்நிழல் புறப்பட மாண்விளக்கு எடுத்துஆங்கு

ஒருமுக எழினியும் பொருமுக எழினியும்

கரந்துவரல் எழினியும் புரிந்துடன் வகுத்து

ஓவிய விதானத்து உரைபெறு நித்திலத்து

மாலைத் தாமம் வளையுடன் நாற்றி

விருந்துபடக் கிடந்த அருந்தொழில் அரங்கத்து

(Silappadikaram, Aragetru Kadhai (99-113)

(Silappadikaram, Aragetru Kadhai (99-113)

Talaikkol, the sacred rod made of bamboo, would be wielded by the dance-master to regulate the dance. The shaft represents Jayanta, Indra’s son who according to legend, was cursed by Sage Agastya to be born as a bamboo stick. Talaikkol was invariably the shaft of the umbrella of the enemy king and was seized in war.

காவல் வெண்குடை மன்னவன் கோயில்

இந்திர சிறுவன் சயந்தன் ஆகென

வந்தனை செய்து வழிபடு தலைக்கோல் (Silappadikaram, Aragetru Kadhai(118-120)

Its joints were set with nine gems and the intervening spaces were covered with plates of pure gold. The poet provides finer details about the ceremony of Talaikkol. On an auspicious day the Talaikkol was washed with the sacred waters of Cauvery brought in golden pitcher and then garlanded and worshiped. Later it was placed in the trunk of the royal elephant adorned with gold plated bands. The drums and other musical instruments would be beaten to proclaim the kings victory. The king along with his live fold retinue and the royal elephant, circumambulated the chariot on which the poet was seated and handed over the talaikkol to him. Then they all went in a procession to the dance hall and placed the talakkol on the dance stage.

From that time on the instrumentalists took their seats as per the laid down order, Madhavi ascended the stage, placing her right foot first and stood near the pillar to the right in confirmation with the norms. The elder dancers assembled by the side of the pillar on the left. The two conventional prayer songs were sung praying for maximizing the virtue and the cease of the vice. At the conclusion of the prayer all the instruments were sounded. The yazh (lute) harmonized with the flute; the tabor sounded in harmony with the yazh; the pot drum was in harmony with the tabor and the anantirikai harmonized with the pot-drum.

A 'mandilam' comprise two strokes and Madhavi danced eleven mandilams without deviating from dancing conventions and thus completed antarakkottu. She then danced the melodic improvisation of the auspicious palai tune without deviating its rigid measure. Demonstrating the four parts of the song, she commenced with three mandilams and concluded with one mandilam; in this way she danced the 'desi-dance' In the same manner she also danced the vaduhu dance, commencing with three mandilams and concluding with one mandilam. In her dance she conscientiously followed the prescription of the dance-scriptures. It looked as if a golden creeper full of flowers was dancing.

The king presented her with his leaf garland, conferring on her the title Talaikkoli in recognition of her skill. He also presented her one thousand and eight gold coins as her one day's fee, according to the prescribed convention. The dancer is now qualified to be called as a ‘professional dancer’ or ‘Natakaganikai’

Reference

- Ancient Indian And Indo-Greek Theatre by M.L. Varadpande. Abhinav Publications, 1981. 157 pages

- Ancient rock paintings discovered at Tirumayam Fort by M. Balaganessin. The Hindu November 23, 2013

- Dance: The Living spirit of Indian Arts. Exotic India. April 2006

- How the Tamil epic extols music and dance. The Hindu March 02, 2001

- Ilango Adigal Silappadikaram. Translated by S.Krishnamoorthy. Bharathi Puthakalayam, 2011. 176 p.

- Isai Tamil inscription in ruins The Hindu March 22, 2012

- Jain Cave Temple at Sittanavasal. HereNow4U.30 July 2015

- Kannaki - Epitome of Chastity. Hub Pages. December 26, 2014

- Koothus in Silapathikaram. Daily News 31 December 2003 (http://archives.dailynews.lk/2003/12/31/artscop14.html)

- Kudumiyanmalai – Inscriptions Tamilnadu Tourism. December 13, 2015

- Matavi’s 11 types of Classical Dance. Tamil and Vedas

- Natya, Nritya and Nritta. Nadanam. http://www.nadanam.com/g_3n.htm

- Project Madurai Silappadikaram Pukar Kandam (http://www.projectmadurai.org/pm_etexts/utf8/pmuni0046.html)

- Quotations from Tamil Epic Silappadikaram (https://tamilandvedas.com/tag/silappadikaram/)Rural murals throw light on life in old Pudukottai. Deccan Chronicle. Dec 23, 2016. (http://www.deccanchronicle.com/131123/news-current-affairs/article/rural-murals-throw-light-life-old-pudukottai)

- Silapathikaram the great tamil epic in short (The Anklet and the Leaves of the Epic). Innland Theatre. February 24, 2011. (http://innlandtheatrechennai.blogspot.in/2011/02/silapathikaram-great-tamil-epic-in.html)

- Tamilnadu's Contribution to Carnatic Music: A Bird's Eye-view by Sundaram, BM (http://tamilelibrary.org/teli/tnmusic1.html)

- Thamizh Literature Through the Ages தமிழ் இலக்கியம் - தொன்று தொட்டு இன்று வரை by Krishnamurti, CR. (http://tamilnation.co/literature/krishnamurti/12present.htm)

- தமிழ் நாடக வரலாறு விக்கிப்பீடியா

- தமிழர் நாடகக் கலை - விக்கிப்பீடியா

- வரலாற்றில் பரதநாட்டியம். இரா.நாகசாமி (http://tamilartsacademy.com/bharata%20natyam.xml)

- நாடக இலக்கியம் (http://www.tamilvu.org/courses/degree/p203/p2031/html/p2031112.htm)

YouTube